Project Overview:

This program started as a pilot, with a pioneering company in the fishery. After demonstrating the success in data collection and value of the data, the government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands made electronic monitoring a license requirement. Individual vessel owners are now required in their license agreements to have a functional EM system installed and operating 100% of the time while fishing. Monitoring elements include compliance, fishing effort and catch/bycatch composition. 2021 is the end of the first 4 year license series with this requirement.

Category: Electronic Monitoring

Project Overview:

Archipelago delivers a full range of EM services to several national fisheries in Australia. These include the Eastern and Western tuna and billfish fisheries (pelagic longline) as well as the groundfish hook and trap fisheries (gillnet and auto-longline. This is a mandatory program contracted by the fisheries agency, funded through service levies collected by government from industry quota holders. This program has been in place since 2014 and provides a full range of EM services to these fisheries on a year-round basis and covers about 80 vessels.

Reprinted with permission from the March 21, 2014 edition of the Daily Sitka Sentinel. Copyright 2014 Daily Sitka Sentinel.

By Shannon Haugland

Sentinel Staff Writer

A group of Sitka and Homer longliners hope to demonstrate this season that electronic monitoring can collect most of the data needed for managing the hook and line fisheries.

The pilot project is part of an ongoing effort by the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association and other longline groups to integrate electronic monitoring as an alternative to having observers aboard boats that longline for sablefish and halibut.

“We want to see EM move ahead,” said Linda Behnken, ALFA executive director. “There have been over 40 EM pilot programs in the U.S. but no programs have been implemented for catch monitoring.”

Five boats homeported in Sitka and five in Homer agreed to carry the electronic monitoring systems for the season, which opened earlier this month. The equipment, installed by the Canadian company Archipelago, includes two cameras mounted on stabilizers that capture the image of every fish that comes over the rail, as well as the GPS coordinates and other data.

The feedback so far from the five Sitka longliners with EM systems aboard has been positive.

“Everything worked fine, and captains have been happy with it,” said Jason Bryan, Archipelago project manager.

The information captured will be analyzed and compiled later, based on what is requested for the project. That could include species of the fish, numbers of fish and the weight, among other options.

Other participating partners in the “limited implementation project” out of Sitka include ALFA, North Pacific Fisheries Association, Petersburg Vessel Owners Association, Southeast Alaska Fishermen’s Alliance, Saltwater Inc., and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

The federal observer program for larger vessels in the domestic fleet has been around since 1990. The expanded program, covering boats 40 feet and up, was approved by the North Pacific Fishery Management Council in 2011 to begin in January 2013. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration manages the observer program, using funding from a 1.25 percent tax on the ex-vessel value of the groundfish and halibut. The tax is assessed on all commercial fishermen, whether they carry an observer or not.

The small-boat fleet has objected to the onboard observer requirement as expensive and intrusive. They hope to show through the pilot project that electronic monitoring – such as the system used in British Columbia and elsewhere in the world – can reduce the need for observers, especially on the smaller boats.

Starting this year vessels 40 to 57.5 feet are in the “vessel selection pool,” where they notify the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration if they plan to fish any time during specific two-month periods. Under this program, a percentage of boats are required to take an observer on every groundfish or halibut fishing trip during each two-month period. Vessel owners are not required to log trips with the agency.

Boats 57.5 feet and up are in the “trip selection pool,” where vessel owners log each fishing trip with the program at least 72 hours in advance of their planned departure. NMFS then randomly draws 15 percent of the trips for an observer.

Operators of longline boats in the 40 to 57.5 foot category point out that their boats lack space to accommodate an observer, and the extra person onboard disrupts day-to-day business and constitutes an added expense of doing business. They argue that the data can be collected in a way that is less burdensome and costly.

ALFA has worked over the past few years on the effort to demonstrate that an electronic monitoring system is effective in collecting data, and providing most of the information that fishery managers need about the halibut and groundfish catches.

“We think having an observer is a whole lot more expensive,” said ALFA Executive Director Linda Behnken. “We’ve been trying for three years to develop an electronic monitoring system as an integrated part of the catch-monitoring program.”

She said thanks to the support of U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, NMFS is working with ALFA on an electronic monitoring cooperative research project.

“Part of that is we installed electronic monitoring systems in five Sitka hook and line boats,” Behnken said. ALFA is working with the Canadian company Archipelago Marine, which has installed hundreds of EM systems in British Columbian boats.

The B.C. longliners have 100 percent coverage of their halibut and sablefish fleet on fixed gear boats and 100 percent observer coverage on trawl boats.

“Our goal is to provide EM as an alterative on boats,” Behnken said. “It’s less burdensome, less costly.” Some boats get released from the observer obligation when they can’t fit an observer on board, which means the boats with an extra berth will be required to carry observers more often, she said. “That puts a burden on them.”

The main goal is to demonstrate that the EM program can be used in combination with other tools – such as dockside monitoring and processors’ information – to collect data for biologists and managers.

“We’re excited to work with Archipelago Marine – they understand how to plan and implement and integrate these systems,” Behnken said. “We’re hoping NMFS works productively with all of us.”

Murkowski included language in an appropriations bill to require NMFS to work with the industry on this issue.

“She’s been super-supportive of the industry,” Behnken said.

This is the second pilot program on electronic monitoring undertaken by ALFA. Boats carried the devices in 2011 and 2012 seasons. It was successful, Behnken said, but EM systems were not integrated into regulations for collecting catch data.

“(NPFMC) needs to take the lead on moving from pilot to a fully integrated component of the catch-monitoring program,” Behnken said.

The way the EM system works is two cameras are mounted, usually on stabilizer poles, aimed at the rail fish from two angles. The cameras are off until a sensor in the hydraulic system triggers the cameras to turn on as fish are brought aboard.

“The system runs the entire time the vessel is at sea,” said Howard McElderry, vice president of EM technology development, and co-founder of Archipelago. “But it’s only recording when fishing activity is taking place.”

The other part of the demonstration program is showing what happens to the information collected, and the ways it can be analyzed to provide information to fishery managers.

“That’s the meat and potatoes of the electronic monitoring program,” said McElderry. The company designs and builds the software for electronic monitoring programs, based on data requested by the client, in many cases fishery biologists and managers.

“It’s a question of what data is required by NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service) to manage the fishery,” McElderry said. “They tell us what they need datawise. … Sometimes the camera is on the whole time, sometimes it’s a hybrid.”

Among the information that can be captured through analysis are the number of fish, the species of the fish, the general area of where the fish are caught, the vessel’s position and the weight.

The main argument against using EM now, instead of relying on observers, is that only observers can collect some types of data. That includes taking biological samples, scale samples and the odelisk, which tells the age. In general, it’s “little things you tuck in an envelope and bring back to the lab,” said Jason Bryan, Archipelago project manager who installed the cameras for the pilot project in Sitka.

B.C. fisheries managers rely on Archipelago to capture and analyze data for the 300 boats in the fixed gear fisheries, including halibut, sablefish, rockfish and dogfish fisheries, as well as the midwater hake trawl fishery and in-shore trawl fishery. The company last year captured 16,000 fishing days using electronic monitoring systems.

“There will always be some observer coverage,” McElderry said.

In British Columbia, there is 100 percent observer coverage in the trawl fisheries; and 100 percent EM coverage in the fixed gear fisheries.

The company is also working on pilot programs for some North Sea, New Zealand and Australian fisheries.

“There’s a general trend trying to improve data for commercial fishing,” McElderry said. “There’s a realization that it’s logistically impractical and costly when you start placing observers on vessels. You run into a host of issues. We’re trying to find a way to use technology to collect data in a way that would be comparable to what an observer would have.”

Dick Curran of Sitka, skipper and owner of the 54-foot F/V Cherokee, is participating in the EM pilot program this season. He said the electronic gear is so unobtrusive that he isn’t even aware that it’s on board. Last year, he had an observer aboard for two months after his boat was chosen in the “vessel selection pool.”

“They’re OK,” he said of the observers. “But for a smaller boat it’s more of a logistics thing with space and stuff like that. Dealing with the camera is just easier.

In 2002, a small-scale demonstration fishery set out to explore individual quota allocation as an alternative management approach in the salmon troll fishery.

Archipelago was contracted by the Area H Gulf Troller’s Association to provide a comprehensive salmon troll monitoring program, collecting information needed to evaluate the potential of this alternative fishery management method.

Electronic monitoring (EM) systems were deployed on four fishing vessels to collect information such as fishing time and location, and documentation of catch by species, number of pieces, and utilization. EM imagery was also used to observe bycatch handling and release procedures. In addition, both at-sea and dockside monitors were provided to collect complementary data that was used to evaluate both the EM systems and the demonstration fishery itself.

Electronic monitoring (EM) systems were deployed on four fishing vessels to collect information such as fishing time and location, and documentation of catch by species, number of pieces, and utilization. EM imagery was also used to observe bycatch handling and release procedures. In addition, both at-sea and dockside monitors were provided to collect complementary data that was used to evaluate both the EM systems and the demonstration fishery itself.

The monitoring program was successful, resulting in a series of expanded testing as a followup.

For fisheries operating near the South Georgia Island wildlife sanctuary, protection of endangered seabirds is a top priority. Tori lines and streamers help keep birds safe, and observers and monitoring systems verify results. Since 2014, Archipelago has been working alongside the Argos Froyanes fishing company to record and review tori line procedures and ensure the region’s strict seabird conservation regulations are being met.

Located 1,400 km East Southeast of the Falkland Islands, the sub-Antarctic Island of South Georgia is home to a vast number of rare and endangered seabirds (including several species of albatross) living amidst the region’s prime fishing grounds.

To help avoid interactions between seabirds and longline fishing vessels, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) oversees a comprehensive set of seabird conservation measures designed to reduce fishing–related seabird mortality.

To help avoid interactions between seabirds and longline fishing vessels, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) oversees a comprehensive set of seabird conservation measures designed to reduce fishing–related seabird mortality.

Implemented and enforced by the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI), these measures require longline fishers to attach weights to branch lines, set gear only at night (under minimal lighting), and deploy tori lines equipped with colorful streamers to help scare birds away from baited hooks.

In 2014, the Argos Froyanes Ltd. fishing company approached Archipelago to explore monitoring alternatives for longline fishing vessels operating in the South Georgia Patagonian Toothfish fishery. Argos’ interest in Archipelago electronic monitoring (EM) systems stemmed from a 2014 MRAG report that described similar Archipelago applications used to monitor bycatch reduction programs within fisheries governed by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) and New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries.

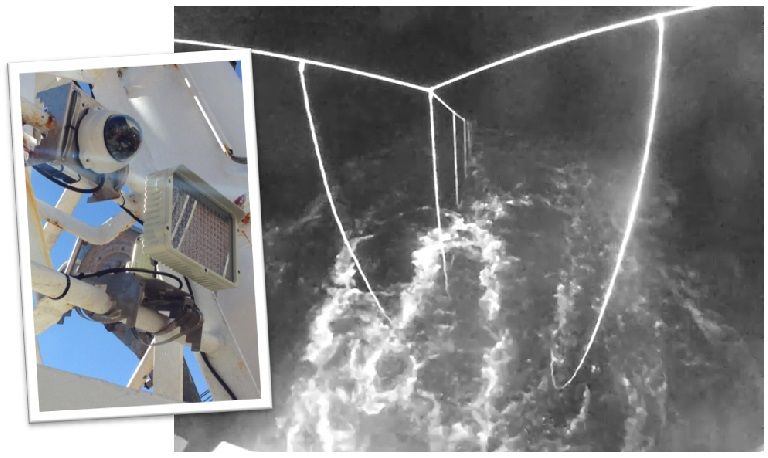

For the South Georgia project, Archipelago installed EM Observe™ monitoring systems aboard two Argos vessels: the F/V Argos Georgia and the F/V Argos Froyanes.

In 2014, the Argos Froyanes Ltd. fishing company approached Archipelago to explore monitoring alternatives for longline fishing vessels operating in the South Georgia Patagonian Toothfish fishery. Argos’ interest in Archipelago electronic monitoring (EM) systems stemmed from a 2014 MRAG report that described similar Archipelago applications used to monitor bycatch reduction programs within fisheries governed by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) and New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries.

For the South Georgia project, Archipelago installed EM Observe™ monitoring systems aboard two Argos vessels: the F/V Argos Georgia and the F/V Argos Froyanes.

Each EM system included a control center, user interface, a pair of rotation sensors (one to detect gear setting and the other to detect hauling), a GPS receiver, a satellite modem, and two cameras (one to capture setting and the other to capture hauling). To comply with the CCAMLR requirement to minimize external illumination, infrared (IR) cameras were a necessity.

The EM systems were installed in March 2014, and configured to collect data throughout the 2014/2015 South Georgia Toothfish fishery seasons. As the electronic monitoring system was not intended to replace human observers in this case, fisheries observers were present on each vessel as well.

During this initial two–year trial, Argos stakeholders had the opportunity to learn more about the systems with remote support from Archipelago staff. Various challenges were identified and resolved through fine tuning, crew training, and ongoing collaboration between Argos and Archipelago.

During this initial two–year trial, Argos stakeholders had the opportunity to learn more about the systems with remote support from Archipelago staff. Various challenges were identified and resolved through fine tuning, crew training, and ongoing collaboration between Argos and Archipelago.

Due to the requirement to set gear at night (using minimal lighting), IR cameras were required; however, IR cameras alone were not sufficient for recording setting activity at the distances required.

While the standard IR cameras could record nighttime activity out to a distance of approximately five to ten metres, the setting operations extended to a range of 80 metres or more. To accommodate these distant viewing areas, EM technicians specified an external IR illuminator for each location.

Based on the promising results of this initial trial, Argos identified two factors as the ongoing focus for this EM project to follow:

- Reduce observer workload by enabling observers to use EM to confirm proper deployment of tori lines and streamers.

- Provide a permanent record of evidence verifying that bird mitigation regulations are being met.

Following the successful conclusion of the initial two–year test period, Argos and Archipelago continue to refine and develop the fishery’s electronic monitoring program.

Next steps include a further integration and refinement of the way infrared video is used to better verify tori line deployments. (Pending approval from the GSGSSI, protocols could be implemented to allow observer access to EM data, and appropriate data tracking and chain–of–custody protocols developed to support the use of EM data as proof of compliance with seabird mitigation measures.)

As a dedicated supporter of sustainable fishing practices, Argos is playing a key role towards the protection of seabirds within this unique and environmentally sensitive region.

For more information on the conservation measures described here, visit the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources web site.

To learn more about the monitoring and review technology, visit the Electronic Monitoring page on this site.